| Just spent the last few days at a technical conference that focused more on cultural change and workflow than bits and bytes, the DevOps Enterprise Summit. It was enlightening, and for the first time in a while, I’m leaving a professional conference energized and hoping to implement some of these ideas. The DevOps community reminds me a lot of the SQL Server community; passionate people who just want to help each other grow. There’s so much good content, and I think most of it will be available via YouTube later.

Armed with my handy dandy Rocketbook (I left my laptop in my hotel room each day purposefully), I scribbled notes fast and furiously. At the end of each day, I tried to capture three things that struck me as important, based on everything I’d heard. Here’s my list, broken apart by day: |

||

Day 1 – Nov 13, 2017

|

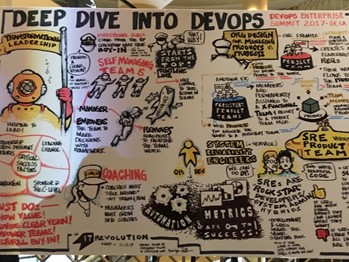

One of the amazing graphic facilitation artifacts done by Christopher Fuller of Griot’s Eye at the conference. |

|

Day 2 – Nov 14, 2017

|

||

Day 3 – Nov 15, 2017

|

||

DevOps

#DevOpsDays #Nashville in the books

Headed back home after a successful Ignite presentation at DevOpsDays Nashville. This was an awesome conference; I’ve blogged in the past about some of my concerns with the single track format, and finding speakers that manage to reach a very diverse audience of engineers, managers, coders, analysts, etc. I had no such concern this time around; I feel like I got something out of every presentation I heard. Very well done.

Headed back home after a successful Ignite presentation at DevOpsDays Nashville. This was an awesome conference; I’ve blogged in the past about some of my concerns with the single track format, and finding speakers that manage to reach a very diverse audience of engineers, managers, coders, analysts, etc. I had no such concern this time around; I feel like I got something out of every presentation I heard. Very well done.

On a personal note, IGNITE TALKS ARE HARD, Y’ALL. 5 minutes, 20 slides is tough to pull off, particularly when you have a penchant for verbosity (editing is NOT my favorite thing to do). I originally proposed this as an Ignite talk because I’m just really starting on my DevOps journey, but in hindsight, I spent WAY more time editing and preparing for this discussion than any SQL Server presentation I’ve ever done. The plus side is that I can reuse a lot of this material in educating my team when discussing the depth of these directions.

Headed home with lots to think about.

Changes… #DevOps, #SRE, and #Management

As many of you know, I’ve been slowly changing focus from database administration to DevOps, management, and service operations. Over the last few years, I’ve been heavily involved with migrating our datacenter to a private cloud infrastructure, and focusing on methods to improve the overall reliability and scalability of my company’s service deliverables. I’ve been a bit of an evangelist for organizational changes, and it’s finally official.

As many of you know, I’ve been slowly changing focus from database administration to DevOps, management, and service operations. Over the last few years, I’ve been heavily involved with migrating our datacenter to a private cloud infrastructure, and focusing on methods to improve the overall reliability and scalability of my company’s service deliverables. I’ve been a bit of an evangelist for organizational changes, and it’s finally official.

On October 1, my job title and responsibilities will officially change from Manager of Database Administration to Senior Manager, System and Network Administration. I think that title’s a bit funny, because I won’t be managing system or networks; our infrastructure is managed by another team, and my team is responsible for applying principles of Site Reliability Engineering to operating our complex business services. Unofficially, we’re calling ourselves Service Reliability Engineering in order to remind ourselves (and others) of our foci:

- Identifying issues that impact the reliability of customer facing services;

- Tracking and documenting complex relationships between applications used in that delivery; and

- Coordinating efforts with other teams responsible for developing and operating those services

The title change itself is a minor issue, but it’s an important distinction to me. It represents a significant shift in my career path. Although I’ve been acting as the IT Operations manager for the last two years, it’s always felt a little odd because I was still known as the DBA manager. With the move to the cloud, most of our administration (like backups, DR, and maintenance) are handled by another group, and we’re responsible for making sure that the applications (all 84 of them) perform appropriately. We’re not coders, but we need to be able to identify coding issues. We’re not network or sys admins, but we need to know how systems work, and be able to propose solutions to scalability issues. We’re not DBA’s, but we need to be able to express data requirements to the new DBA team. In short, we’re an integration point for a loosely coupled set of applications.

I plan to blog more on Service Reliability Engineering in the future, but for now, I’m excited about what’s happening.

Presenting at #DevOpsDays #Nashville

Very excited to be presenting an Ignite talk at #DevOpsDays #Nashville (October 17-18, 2017): Tactical Advice For Strategic Change In A Brownfield

Very excited to be presenting an Ignite talk at #DevOpsDays #Nashville (October 17-18, 2017): Tactical Advice For Strategic Change In A Brownfield

It’s only a 5 minute presentation (20 slides; slides change every 15 seconds), but I’m stoked about it. It’s going to be my first DevOps talk that has absolutely nothing to do with SQL Server; finally starting to go in a new direction, and focus on Culture, Lean, and Sharing. It’s a great little conference, and I’m grateful to go back for my second year (this time as a speaker).

Now, I just got to develop the slide deck J

#DevOpsDays & #SQLSaturdays

I’ve been meaning to write this post for a while, but life rolls on, as it always does. I had the privilege of attending DevOpsDays Atlanta back in April. This was my second DevOpDays event to attend (the first being Nashville), and overall, I’ve enjoyed the events. However, as a long-time organizer and speaker with the SQL Saturday events, it’s hard for me not to compare my experiences between the two conferences. They’re both community-run, low-cost, voluntary technical events; however, there were some things that I really like about the DevOpsDays format (and some things I wish were different).

Cost

The cost models of the two conferences are different; in short, SQLSaturday’s are free to the attendees (although a lunch fee is usually provided as an optional service), and DevOpsDays charges a small fee ($99-$150). Both rely on sponsors to pick up the tab for the bulk of the expenses (usually location fees). Speakers are volunteers, as well as event management staff. The benefit for the attendee is guaranteed swag (an event t-shirt is typical) and a great lunch (food was fantastic at DevOpsDaysAtlanta).

Charging a higher fee does a couple of things; it allows organizers to get a more accurate attendance estimate; if an attendee pays more to go to a conference, it’s more likely that they’ll show up. This has a trickle effect on luring sponsors; it’s easier to justify sponsoring an event if you know that you’re going to get a certain amount of foot traffic. A fee also guarantees amenities that are important to technical folk; good Wifi, and livestreams (although sessions weren’t recorded at the Atlanta DevOpsDays event). You can also direct some of those funds to getting a premier meeting space.

On the other hand, a free event with a nominal lunch has the potential of bringing in a much larger audience; DevOpsDays Atlanta was hosted in a 230-seat theatre, so attendance was probably around 250 (with standing room, vendors, and speakers). Last year’s Atlanta SQL Saturday had over 600 attendees, and this year’s event had slightly over 500 attendees. Attendance counts shouldn’t be considered a metric of superiority, but it does provide a different incentive for pursuing sponsors. As an attendee, I like the SQLSaturday model; as an organizer, I like the DevOpsDays model.

Parent Organization Involvement

DevOpsDays is a highly decentralized model (true to the agile underpinnings of the movement). The parent organization appears (from the outside) to be very hands off; local event organizers handle their own sponsorships, registration, and other details. This allows for a lot of fluidity when it comes to branding, networking, etc. For example, see the differences in advertising logos for the DevOpsDays organization, the Atlanta 2017 event, and the upcoming Nashville 2017 event:

| DEVOPSDAYS (GENERIC) | ATLANTA 2017 | NASHVILLE 2017 |

|

|

|

In contrast, PASS (the Professional Association for SQL Server) retains tight control over the marketing of SQLSaturday; registrations and event planning are handled by their internally-developed tools, and the branding has recently evolved to provide a more consistent association with the parent organization (although not without some concerns).

| PASS LOGO | SQLSATURDAY LOGO |

|

|

From an attendee perspective, branding probably doesn’t make much of a difference; however, the tools used for registration are highly visible. Both DevOpsDays events I attended used EventBrite, a well know tool for managing, well, events. SQLSaturday relies on a custom registration site that has improved over time, but still often leaves attendees confused (despite all the best guidance from organizers). Furthermore, if a SQLSaturday event has a precon, those events are usually managed by EventBrite, which leads to an additional disconnect between the precon event and the actual SQLSaturday. Despite my love for SQLSaturdays, I think the DevOpsDays approach to branding and tooling is better.

Educational Delivery Format

One area that SQLSaturday feels more comfortable to me is the format of the sessions. SQLSaturdays typically follow the traditional multi-track model in a single day (not counting pre-cons), where attendees can choose from multiple sessions at the same time; for example, SQLSaturday Atlanta 2017 had 10 concurrent tracks, each with sessions lasting about an hour. Note that this format is not required; smaller events may only have a single track, or have multiple tracks with longer sessions.

In contrast, the DevOpsDays standard of delivery is multiple days, with a single track in the morning of longer talks, followed by a single-track of short talks (“Ignites“), and then open-space sessions in the afternoon. For me, this is a mixed bag of effectiveness; bringing everyone in the conference together to hear the same discussion can (in theory) promote better cross-communication between the various stakeholders in the DevOps audience. For example, having managers and deployment specialists hear a programmer discussing pipelines may promote perspective-taking, one of the fundamentals of good communication. In reality, however, my experience has been that many presenters don’t do a great job of relating to all of the stakeholders in the audience, making it difficult to bridge that gap. Granted, I’ve only been to two events, but of the 16 main talks that I heard across the two events, about half of them seemed relevant to me. Ignites have some of the same limitations, but the time constraints mean that they hold attention spans for longer.

Most people either love or hate open spaces; letting the audience drive discussions is a great concept in theory; in reality, discussions are typically dominated by a few extroverts in the group, and most people merely observe. Although there are usually self-appointed moderators, the dynamic selection of topics just prior to the discussion makes it difficult to engage or guide. When they work, they work well; however, too often open spaces lend themselves to the seven-minute lull Ideally, I think the most effective method of delivery would be a blended approach; a couple of keynote sessions in the morning, followed by a few Ignite sessions. Do multiple tracks in the afternoon, including open-space discussion, both free-form and guided. However, this is mostly a matter of personal preference; I’d love to try it and see what people think of it.

Conclusion

I’m enjoying the transition of my career away from being a SQL Person to a DevOps person; both communities seem vibrant and engaged, and I plan on attending more DevOpsDays conferences in the future (and perhaps even help with planning one). Events like these offer a lot of opportunity to learn high-quality material in a low-cost setting, and I only expect them to get better (or I’ll get better) over time.

#SQLSatATL, #DevOps, #Cloud, & the Future of the DBA

Last weekend was SQLSaturday Atlanta 2017, and I was not only an organizer, but a presenter. In the future, I’ll need to balance that a little better (especially when we’re dealing with a lot of unknowns for the day, like a new building). Overall, I think my presentation went well; had a lot of great hallway conversations with folks later, and got some good feedback. You can find the slide deck here, or look on the Code, etc tab above.

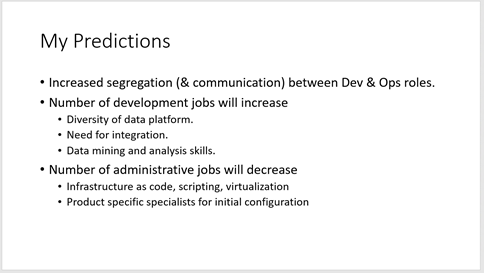

However, during my presentation, a couple of questions came up that I didn’t have a great answer for; mostly it was revolving around the first bullet point on this slide:

Why, if DevOps as a philosophy encourages better communication between development and operations, do I believe that there will be increased segregation between those roles? I fumbled for an answer during the presentation, but then went back and realized what I left out in my explanation, so I thought I’d take a stab at rebuilding my argument and explain where I was going with this:

DevOps is built on a Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA) model.

Services logically represent business activities; they are self-contained, and the inner workings of each service are opaque to the consumers. Services can be built using other services, but that rule of opacity stays true; when you consume a service, you don’t care what it’s doing under the covers. It just has to provide a consistent output when given a consistent input.

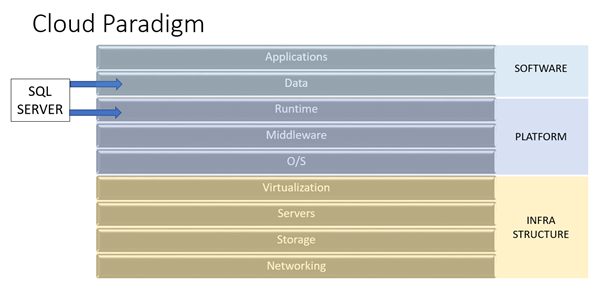

The Cloud Paradigm is also built on a SOA model.

Software-as-a-Service is built on a Platform-as-a-Service, which is in turn built on an Infrastructure-as-a-Service. Communication between service layers must be consistent and repeatable, but processes and procedures within each services should be opaque. Furthermore, the consumers of a service are not the same; for example, if you have a web portal displaying account information to a client. The client consumes Software-as-a-Service; they just want to see their account information. They don’t care how many servers are involved or how the network is laid out. Software-as-a-Service consumes from the Platform layer; they may have a requirement that they use a particular database system, or OS, but specific configuration isn’t exposed to them. Software engineers define performance expectations (e.g, “we need to commit 1000 transactions per second”), and leave it up to the Platform (and Infrastructure) engineers to meet that expectation.

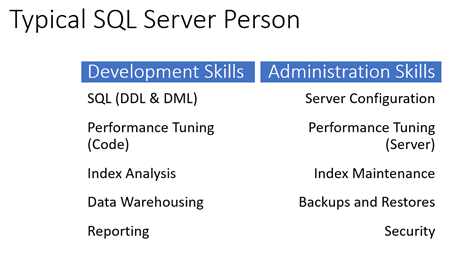

The traditional tasks associated with SQL Server Database Administration can be roughly divided into two roles: Development and Administration (Operations).

From this slide, I outline the general breakdown between skills:

SQL Server as a product spans the top two layers of the Cloud Paradigm:

Basically, I believe that traditional development skills belong to the Software-as-a-Service Layer, and traditional administration skills belong to the Platfom layer.

So by segregation of responsibilities, I mean that as companies embrace the Cloud paradigm, the current role of a DBA will fork into both Software-as-a-Service engineering (Dev) and Platform-as-a-Service engineering (Ops). I need to clarify that thought more in future presentations, because I may be using those terms differently than others would.

Thanks for reading, and if you attended, thanks for coming!

-Stu

#FAIL

There’s been some great discussion in the #SQLFamily after Brent Ozar published a recent blog post: I Failed 13 College Courses. Lots of comments on Facebook about it, and other people soon came forward with their own brief tales of academic failure (and subsequent successes). I was particularly touched by Mike Walsh’s video (What Advice Should I Share on Career Day?), where he talked about dropping out of high school. Most of the conversations were about the struggles in academia, but there was real underlying thread: You can succeed and be happy after facing failure.

There’s been some great discussion in the #SQLFamily after Brent Ozar published a recent blog post: I Failed 13 College Courses. Lots of comments on Facebook about it, and other people soon came forward with their own brief tales of academic failure (and subsequent successes). I was particularly touched by Mike Walsh’s video (What Advice Should I Share on Career Day?), where he talked about dropping out of high school. Most of the conversations were about the struggles in academia, but there was real underlying thread: You can succeed and be happy after facing failure.

I’m friends with a lot of smart, successful people, and for those of us that are engaged in information industry, failing at an intellectual exercise (like college or high school) can be perceived as a mark of shame. I think what Brent, Mike, and others are showing is that recovering from failure is not only possible, but normal. We all fail at something, and that often puts on a new path to figuring out something else. Failure teaches us more than success.

My Story…

(Note: I just realized that my last blog post touched on this story briefly. Must be on my mind a lot lately.)

I didn’t fail in high school (WMHS, 1989).

I didn’t fail during my Bachelor’s degree (ULM, 1993 – B.A, RadioTVFilm Production).

I didn’t fail during my first Master’s degree (ULM, 1995 – M.A, Communication).

I didn’t fail on my coursework for my doctoral degree. (UGA, PhD coursework completed in 1999).

Nope. I waited until I was 28 years old (with a wife and two kids depending on me) to fail at my first academic exercise. I bombed my doctoral comprehensive exams not once, but twice over a 6 month period. In April of 2000, I was waiting outside my major advisor’s office to discuss my options for a third attempt. I waited for two hours, brooding over the shape of my life at the moment. She never came, so I walked out the door and didn’t go back (stopping at a bookstore on the way home to purchase two books on SQL). I didn’t hear from her until a few years ago when she friended me on Facebook, and we’ve never really discussed it. I’m happy, and she’s moved on to greater successes as well.

As an aside to this story, I had been working at the American Cancer Society while going to school; my official title on most publications was Research Assistant, but I was the shadow DBA for the Behavioral Research Center. I had been working with Microsoft Access to manage contact information for cancer registries as well as using SPSS with SQL to analyze data. I parlayed that interest in data management into a new job in August of 2000; I had decided that I wasn’t cut out for anything academic, and I wanted to move into IT full time.

I did go back in 2001 to finish a second Master’s degree in Education (UGA, 2002 – M.Ed. Instructional Technology). Yes, I have three college degrees, and none of them are in information Technology.

What I Learned…

Lots of lessons I picked up out of this.

First, I learned that the fear of failure often motivates me to pick the easier path. Looking back over my academic career, I’ve always been smart enough to know what my limitations are, and lazy enough to not challenge them. I got a degree in Radio Production, not just because I enjoyed the theatrical end musical elements but also because I knew I didn’t have to take harder courses (like Chemistry, Physics or Calculus; all of I which I had managed to avoid in High School). I used to think it was working smarter, not harder; in hindsight, I just didn’t want to fail.

Second, a fear of failure often blinds me from looking at the bigger picture. When I’m scared that something is going off the rails, my instinct is to drive forward at full speed and force it to succeed. Over time, I’ve learned to be sensitive to those warning signs, and try to put the brakes on and redirect. At several points in my graduate career, I knew that I was in the wrong field. But I had a job in academic research, and I had never failed before, so I was going to see this through and will it to be. That obviously didn’t work.

Third, fail early, because failing late in the game is expensive. I racked up over $120,000 in student loans in my doctoral program; if I had recognized early on that I wasn’t going to be happy, I could have avoided that. If I had challenged myself earlier with smaller risks, I might have predicted that academia wasn’t for me. Hindsight is amazingly clear; in the thick of it, however, I’ve learned that it’s best to take small risks when possible, and fail often. Failing at something gives you two choices: you challenge yourself to try something different and succeed in the future, or you curl up in a ball and “accept your limitations”. It’s easier to bounce back when the consequences of the failure are small.

Summary

I’m no guru; I’m just a guy trying to figure it all out just like you. I’ve gone on to have other epic failures, as well as some incredible successes. I will say that my own personal journey has resonated with my perspectives on software and service development recently. Below are some great reads about failure.

The Technical Manager

I used to present a session called Managing a Technical Team: Lessons Learned (Alexa: Remind me to update and submit this session again); the point of it was to reflect on some of the lessons I learned early in my career transitioning from a database developer into a management position. I was trying to give a view from the trenches, mostly to help other folks get a perspective on what it’s like to fumble through a career change. Management, like development, is a process of learning and continuous improvement; the difference is that other people have some expectation that you know what you’re doing (and often, you don’t). Inevitably, I’d get asked some version of this question:

I used to present a session called Managing a Technical Team: Lessons Learned (Alexa: Remind me to update and submit this session again); the point of it was to reflect on some of the lessons I learned early in my career transitioning from a database developer into a management position. I was trying to give a view from the trenches, mostly to help other folks get a perspective on what it’s like to fumble through a career change. Management, like development, is a process of learning and continuous improvement; the difference is that other people have some expectation that you know what you’re doing (and often, you don’t). Inevitably, I’d get asked some version of this question:

“Can I still be technical and manage a team effectively?”

I used to have a quasi-canned answer, something along the lines of “at some point you must choose your path; management is about people, not technology”. I still kind of believe that, but recent experiences in my own career path have caused me to reconsider giving an answer. Instead, I’ve started asking the questions:

“Why does it matter? What’s your goal for your career? What do you think you should do?”

The truth is, I don’t know what’s best for you, but I trust that you do (that satisfies my libertarian soul). Everybody’s got different experiences, different beliefs, different goals, and different circumstances. When you bundle those things together, it makes for a very complex decision tree; even a simple question about how you want to conduct your day-to-day affairs becomes overwhelming for someone sitting on the outside to answer. That being said, I still want to help, so I thought that I would share some of my decision factors using the four buckets above.

Experiences

Here’s some of experiences that have gotten me to this point:

- I don’t have a technology-related degree; I have a BA in RadioTVFilm Production, a MA in Communication, and a MEd in Instructional Technology. I got into database work when I flunked out of a PhD program in Health Communication (and salvaged some of those hours into the MEd). I had failed my comprehensive exams twice, and had a meeting set up with my advisor to discuss a third attempt. She never showed; I drove off campus that night, bought some books on SQL and relational design (having done stats work as a grad student), and started looking for a job.

- In my first IT job, I worked for a good manager (a developer running a support organization). When he left, I worked for an awful manager (a project manager who had no clue about anything related to computers). I try to emulate the former and check my actions to make sure I’m not acting like the latter.

- I’ve been with the same company for almost 15 years since then. Different roles, different responsibilities, different owners.

Beliefs

These are some of the core beliefs I have about management and technology; these will be tough to change.

- Management is more about people than tools.

- Management should be more strategic than tactical. While a team may be responsible for specific operations, the manager of that team should understand the unit’s role in the bigger picture.

- Technology is used to solve business problems; a good manager will focus more on solving the problem than on the tools used at any point in time. SQL Server is the tool I’m accustomed to using, but the problems I’ve been focused on lately aren’t database problems (they’re IT infrastructure and networking issues).

Goals

Goals are tough for me, because I believe they should be a mixture of both long-term and immediate. As such, they change more often than you would think (at least for me).

- I want to be forward-thinking; I want to keep being exposed to new tools and technologies.

- I want to be compensated well, and I want to continue gaining new responsibilities.

- I want to feel like I’m making a difference; I’m not interested in continually addressing the same problems over and over again. I want to make a change and move on.

Circumstances

Everybody’s got different external factors that influence their decisions; managers are no different. For me, the following things are true:

- I’ve been a remote worker for the last 8 years; it would be tough for me to go back to having a daily commute.

- I’m project focused, not time-focused. I like having flexibility to get things done without a set schedule.

- I’m a dad, and time with my kids is critically important. That means that I’ve had to pass up on opportunities because I’d rather take time for them.

What does this all mean?

For me, it means that I don’t want to be a single-technology manager; I want to figure out how to make technology work for business, even if it’s a technology that I’m unfamiliar with. The logistics of scale means that I can’t be the single source of authority when it comes to implementing technical solutions. I scale out by relying on my team to be the experts, and I want to keep building teams that can handle lots of different problems.

More to come later.

#DevOps: Embrace the Ops

If you’re at all in touch with the DevOps community, you’re probably aware of the GitLabs Incident on 1/31/2017; I won’t spend too much time rehashing it here, but GitLabs has done a great job of being transparent about the issue and their processes to recover. Mike Walsh (Straight Path Solutions) wrote a great blog post about it entitled DevOps: Don’t Forget The Ops, which covers a lot of ground from a database administration perspective. Mike ultimately ends up with three specific action items for DevOps teams:

- Plan to Fail (so you don’t)

- Verify Backups (focus on restores, not backups)

- Secure your environment (from yourself).

I agree with all of these ideas; I think Mike is spot on about the need to Remember the Ops in DevOps. However, I want to go a step further, and encourage DevOps adoptees to Embrace the Ops.

What do I mean by that? Let me start with this; Brent Ozar posted this on Facebook yesterday (the image will take you to the job description):

Now, it’s obvious that GitLabs had a backup strategy (they detailed it in their notes), so I don’t mean to imply that they didn’t expect administrative tasks from their database people, but I do think we can infer that administrative tasks were not prioritized as much as other tasks (high availability, performance tuning, etc.). Again, we know that GitLabs had strategy for backups, so it appears that this is a cultural issue (at least based on this flimsy evidence and the outage). And to some degree, that’s understandable; one of the longest running challenges on the operations side is being labeled as a cost center as opposed to development being viewed as a revenue generator. This perception is pervasive in traditional IT shops, so it’s probable that even Unicorn shops share some of this mentality. Development (new features) makes money; Operations cost money.

However, in a true DevOps model, the focus is on delivering quality services to customer, faster. New features may bring new clients, but reliable service retains clients; both are revenue generating. So while it may add some cost to deliver quality service to customers, cutting corners in operations risks impacting the bottom line. From this perspective, I’m arguing that DevOps shops should not only remember the ops, they should embrace it. The entire value stream of a business service includes people, procedures, and technology split into teams; the fewer the teams per service, the fewer silos. So how do we embrace the ops?

- If Ops is part of the Value Stream, then apply consistent Development principles to it. I’ve written before that “we are all developers“, and I believe that; administrators are creative folk, just like application developers. Operations includes backup, monitoring, and validation. We should apply development principles to these operations, like creating reusable scripts, finding opportunities for automating validation, and logging (and investigating) errors with that pipeline. We should use source control for these tools, and treat the operations pipeline like any other continuous integration project (automate your backup, automate your restores, and log inconsistencies).

- Include operational improvements as part of the development pipeline. I’m borrowing a lot from Google’s SRE model; SRE is what you get when you treat operations as if it’s a software problem (see point 1 above). However, the SRE model is usually a self-contained bubble within operations; they have their own pipelines for toil reduction. I think if DevOps wants to truly embrace operations, developers need to include toil reduction in the service delivery pipeline. If operations folks have to flip 30 switches to bring an app online, development should make it a priority to reduce that (if possible). It goes back to the fundamental rule for DevOps: communicate. Help each other resolve pain points, and commit to improving everything in the value stream.

- Finally, balance risk and experimentation with safety. Gene Kim’s The Phoenix Project provides the Three Ways, and the Third Way is all about creating a culture that rewards risk and experimentation. This is great for developers; try something new, and if it breaks, you can deliver a fix within hours. However, as the GitLabs incident shows, some fixes can’t be delivered, and risk needs to be mitigated by secure data handling processes and procedures. While I’m a big fan of controlled failures (e.g., shutting a server down hard in order to see what the impact is), you don’t do that unless you can test it in a lab first and make sure you have good mitigating option (how do you recover? What error messages do you expect to see? Are you sure your backup systems are working?). Don’t forsake basic safety nets while promoting risk; you want competitive advantages, but you also want to stay in business.

5 #DevOps Books I plan to finish this year

New Year. Resolutions, etc. 🙂

I’m notoriously bad about starting a book and never finishing it, particularly when it’s a technical book. My goal this year is to finish the following 5 books:

|

The DevOps Handbook: How to Create World-Class Agility, Reliability, and Security in Technology OrganizationsGene Kim is perhaps best known for his novel “The Phoenix Project”, which lays out the fundamental precepts for DevOps. The Handbook (by Kim, Patrick Debois, John Willis, and Jez Humble) gets great reviews, and I think it does a good job of translating theory into practice. I’ve only finished about a third of it, so I’ve still got a lot of reading left to do, but I hope to finish it soon. |

|

Site Reliability Engineering: How Google Runs Production SystemsThis one might be a little easier to cheat on my goal; I’ve already read most of it. It’s a collection of papers written by various SRE’s within Google, and gives some great insights into their vision of applying developmental principles to operation problems. While it could be argued that the SRE model is distinct from DevOps, there’s enough overlap that it makes sense to apply these techniques to my DevOps study. |

|

Level Up Your Life: How to Unlock Adventure and Happiness by Becoming the Hero of Your Own StoryThis one’s a bit of a stretch for most DevOps folks, but if you think of it an approach to personal continual improvements, then it makes sense why this book belongs in a DevOps collection. I started reading this one last year, and quickly off the bandwagon. My goal is to try and finish it by the middle of the year, and hopefully begin to apply some of the principles to my personal and professional challenges. |

|

The Art of Capacity Planning: Scaling Web Resources in the CloudI heard John Willis at DevOpsDays Nashville this year, and he recommended following and reading John Allspaw (among other people); the second edition of this book is coming out this year, so I’ll probably wait till it arrives. While I don’t do much with either web or cloud development, the principles of scaling is relevant to all kinds of applications. |

|

Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex WorldDamon Edwards actually recommended this book during a webcast I saw a couple of months ago, and while it’s not a technical book, it speaks to the art of transforming a large, complex organization with entrenched policies into a nimble, responsive team. Brownfield to greenfield (with military references). |