I’ve been meaning to write this post for a while, but life rolls on, as it always does. I had the privilege of attending DevOpsDays Atlanta back in April. This was my second DevOpDays event to attend (the first being Nashville), and overall, I’ve enjoyed the events. However, as a long-time organizer and speaker with the SQL Saturday events, it’s hard for me not to compare my experiences between the two conferences. They’re both community-run, low-cost, voluntary technical events; however, there were some things that I really like about the DevOpsDays format (and some things I wish were different).

Cost

The cost models of the two conferences are different; in short, SQLSaturday’s are free to the attendees (although a lunch fee is usually provided as an optional service), and DevOpsDays charges a small fee ($99-$150). Both rely on sponsors to pick up the tab for the bulk of the expenses (usually location fees). Speakers are volunteers, as well as event management staff. The benefit for the attendee is guaranteed swag (an event t-shirt is typical) and a great lunch (food was fantastic at DevOpsDaysAtlanta).

Charging a higher fee does a couple of things; it allows organizers to get a more accurate attendance estimate; if an attendee pays more to go to a conference, it’s more likely that they’ll show up. This has a trickle effect on luring sponsors; it’s easier to justify sponsoring an event if you know that you’re going to get a certain amount of foot traffic. A fee also guarantees amenities that are important to technical folk; good Wifi, and livestreams (although sessions weren’t recorded at the Atlanta DevOpsDays event). You can also direct some of those funds to getting a premier meeting space.

On the other hand, a free event with a nominal lunch has the potential of bringing in a much larger audience; DevOpsDays Atlanta was hosted in a 230-seat theatre, so attendance was probably around 250 (with standing room, vendors, and speakers). Last year’s Atlanta SQL Saturday had over 600 attendees, and this year’s event had slightly over 500 attendees. Attendance counts shouldn’t be considered a metric of superiority, but it does provide a different incentive for pursuing sponsors. As an attendee, I like the SQLSaturday model; as an organizer, I like the DevOpsDays model.

Parent Organization Involvement

DevOpsDays is a highly decentralized model (true to the agile underpinnings of the movement). The parent organization appears (from the outside) to be very hands off; local event organizers handle their own sponsorships, registration, and other details. This allows for a lot of fluidity when it comes to branding, networking, etc. For example, see the differences in advertising logos for the DevOpsDays organization, the Atlanta 2017 event, and the upcoming Nashville 2017 event:

| DEVOPSDAYS (GENERIC) |

ATLANTA 2017 |

NASHVILLE 2017 |

|

|

|

In contrast, PASS (the Professional Association for SQL Server) retains tight control over the marketing of SQLSaturday; registrations and event planning are handled by their internally-developed tools, and the branding has recently evolved to provide a more consistent association with the parent organization (although not without some concerns).

| PASS LOGO |

SQLSATURDAY LOGO |

|

|

From an attendee perspective, branding probably doesn’t make much of a difference; however, the tools used for registration are highly visible. Both DevOpsDays events I attended used EventBrite, a well know tool for managing, well, events. SQLSaturday relies on a custom registration site that has improved over time, but still often leaves attendees confused (despite all the best guidance from organizers). Furthermore, if a SQLSaturday event has a precon, those events are usually managed by EventBrite, which leads to an additional disconnect between the precon event and the actual SQLSaturday. Despite my love for SQLSaturdays, I think the DevOpsDays approach to branding and tooling is better.

Educational Delivery Format

One area that SQLSaturday feels more comfortable to me is the format of the sessions. SQLSaturdays typically follow the traditional multi-track model in a single day (not counting pre-cons), where attendees can choose from multiple sessions at the same time; for example, SQLSaturday Atlanta 2017 had 10 concurrent tracks, each with sessions lasting about an hour. Note that this format is not required; smaller events may only have a single track, or have multiple tracks with longer sessions.

In contrast, the DevOpsDays standard of delivery is multiple days, with a single track in the morning of longer talks, followed by a single-track of short talks (“Ignites“), and then open-space sessions in the afternoon. For me, this is a mixed bag of effectiveness; bringing everyone in the conference together to hear the same discussion can (in theory) promote better cross-communication between the various stakeholders in the DevOps audience. For example, having managers and deployment specialists hear a programmer discussing pipelines may promote perspective-taking, one of the fundamentals of good communication. In reality, however, my experience has been that many presenters don’t do a great job of relating to all of the stakeholders in the audience, making it difficult to bridge that gap. Granted, I’ve only been to two events, but of the 16 main talks that I heard across the two events, about half of them seemed relevant to me. Ignites have some of the same limitations, but the time constraints mean that they hold attention spans for longer.

Most people either love or hate open spaces; letting the audience drive discussions is a great concept in theory; in reality, discussions are typically dominated by a few extroverts in the group, and most people merely observe. Although there are usually self-appointed moderators, the dynamic selection of topics just prior to the discussion makes it difficult to engage or guide. When they work, they work well; however, too often open spaces lend themselves to the seven-minute lull Ideally, I think the most effective method of delivery would be a blended approach; a couple of keynote sessions in the morning, followed by a few Ignite sessions. Do multiple tracks in the afternoon, including open-space discussion, both free-form and guided. However, this is mostly a matter of personal preference; I’d love to try it and see what people think of it.

Conclusion

I’m enjoying the transition of my career away from being a SQL Person to a DevOps person; both communities seem vibrant and engaged, and I plan on attending more DevOpsDays conferences in the future (and perhaps even help with planning one). Events like these offer a lot of opportunity to learn high-quality material in a low-cost setting, and I only expect them to get better (or I’ll get better) over time.

As I’ve

As I’ve

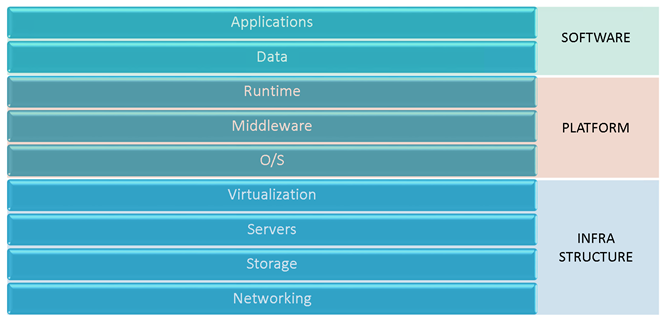

The cloud paradigm talks about breaking the computing stack up into various services, each acting as a black box to the level above it; Software as a Service is built on top of a Platform as a Service, which in turn is built on top of an Infrastructure as a Service. As enterprises begin to embrace the cloud, they will reorganize resources along these lines. Why? Because it lays the foundation for consolidating resources where it counts, and allows for future portability. In other words, companies can start at the bottom of the stack, and port their Platform and Software services over to cloud providers without significant alteration of those upper level. Likewise, as technology matures, migrating the Software layer to a new Platform provider will get easier over time (

The cloud paradigm talks about breaking the computing stack up into various services, each acting as a black box to the level above it; Software as a Service is built on top of a Platform as a Service, which in turn is built on top of an Infrastructure as a Service. As enterprises begin to embrace the cloud, they will reorganize resources along these lines. Why? Because it lays the foundation for consolidating resources where it counts, and allows for future portability. In other words, companies can start at the bottom of the stack, and port their Platform and Software services over to cloud providers without significant alteration of those upper level. Likewise, as technology matures, migrating the Software layer to a new Platform provider will get easier over time (

There’s been some great discussion in the

There’s been some great discussion in the  I used to present a session called

I used to present a session called  Been a while since I’ve posted, so I thought I’d try to put down some thoughts on a lightweight topic. I’m a full-time remote worker; I have been for the last 10 years). My company has embraced remote workers, and provides lots of tools for people to contribute from all over the country (including the wilds of North Georgia); tools include instant messaging clients, VOIP, remote presentation software, etc. Document sharing and discussion is easy, but as you probably know, DevOps is as much about relationship building as it is about knowledge sharing. How do you minimize silos between teams when teams aren’t physically located near each other?

Been a while since I’ve posted, so I thought I’d try to put down some thoughts on a lightweight topic. I’m a full-time remote worker; I have been for the last 10 years). My company has embraced remote workers, and provides lots of tools for people to contribute from all over the country (including the wilds of North Georgia); tools include instant messaging clients, VOIP, remote presentation software, etc. Document sharing and discussion is easy, but as you probably know, DevOps is as much about relationship building as it is about knowledge sharing. How do you minimize silos between teams when teams aren’t physically located near each other? Last week, I had the pleasure of attending my first DevOps conference (

Last week, I had the pleasure of attending my first DevOps conference (