True story: when I was in college, I was the lead singer (if you can call it that) for a goth rock Christian rave band called Sandi’s Nightmare. I had zero musical talent, and relied solely on the strengths of my band-mate (Brad; you still rock); however, while my singing ability was dubious at best, I was pretty theatrical. We had a total of 3 awesome shows before we moved on to other things, but it was a lot of fun while it lasted. Our biggest hit was a cover of Lust Control’s Dancing Naked, a fantastic little number about David’s celebration of the ark returning; his passion and excitement overwhelmed his embarrassment.

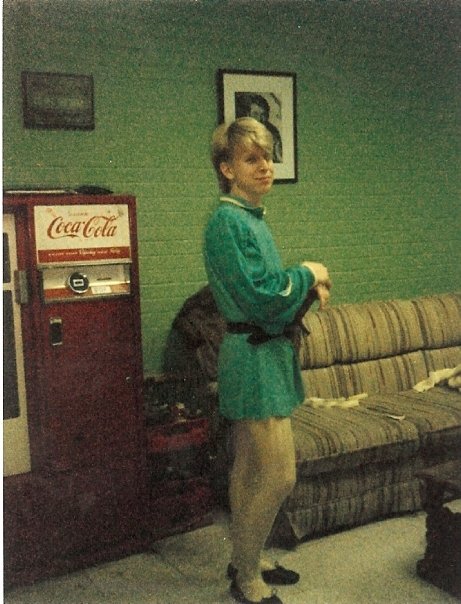

I promise, I’m not making this stuff up; it was pretty edgy for the Bible belt of Northeast Louisiana in the early 90’s. I mean, I had an earring and everything. The point of this post (besides reveling in my musical abilities and tastes of 25 years ago) is that sometimes we just need to be naked.

Let me explain; I made choices that in hindsight are difficult to defend (like my haircut). However, there was a reason for the choice at the time, and even though it may not have been the greatest idea, I’ve learned something from every experience I had. While there are things that I would do differently if given the choice and knowledge I have today, I don’t regret many things. That’s what the metaphor of nakedness is all about; being open and honest about not only your successes, but your choices along the way. You can’t change the past, but you can learn from it.

Becoming a Naked Developer

I’ve spent most of my professional career as a SQL developer working for one company (13 years in November); I was the first developer hired by that company, and my job was to build an integration platform transforming syslog data into reports, all on a shoestring budget. I strung something together in a couple of weeks, and in the first month, I took a process that normally took two weeks to do by hand down to a day; my boss threatened to kiss me (I was flattered, but declined).

Was it pretty (the code, not the boss)? No. Was it successful? Yes.

Fast forward a couple of years to 2004: I’m a member of small team building a solution to analyze more data than I’ve ever seen in my life (terabytes of data from firewalls and Windows machines); we had to import and semantically normalize data in near-real-time. We built a solution using DTS, and then moved it to .NET and MSMQ.

Was it pretty? No. Was it successful? Yes. Part of that code is still being used today, and my company has thrived off of it. We were acquired by a larger company 8 years ago, and we’ve kept moving forward.

Every few years, we’d talk about doing a rewrite, and we’d bring in some outside expertise to evaluate what we’ve done and help us come up with a migration plan. Some consultant would come in, look at what we did, and shake their heads at us. Each time, we (the remaining original developers) would attend meeting after meeting as our code was dissected and judged; we sat naked (metaphorically) in front of a team of experts who told us everything that was wrong with the choices that we made. At the end of each visit, we’d regroup and complain about the agony of judgement. In all honesty, we would have done things differently, given our current experience (and modern technology). However, the simple truth is: we won the day. We continue to win the day.

During some of these initial code reviews, the consultants were jerks. They’d spend a lot of time bemoaning how horrid everything was; I’d be embarrassed and try to explain what I would have done differently if only I had the time. The consultants would eventually propose some complex solution that would cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to implement. Our company would consider the offer, stick it in a file somewhere, and we’d keep on keeping on. Clunky code that works is better than expensive code with the same outcome.

Over time, I learned to live with the embarrassment (as you can tell from this post); I started listening to what the consultants would say and could quickly figure out which ones had good advice, and which ones were there to just be seagulls. People that focused on solving the immediate problems were much easier to talk to than the people who wanted to rip out everything and start over. Don’t get me wrong; sometimes you need to start over, but there is a cost associated with that decision. It’s usually much easier to start where you are, rather than trying to reinvent the wheel.

What’s my point?

First and foremost, don’t dwell on your past mistakes. If you can honestly say that you built something that worked within the constraints of the time period, no matter how clunky or silly it seems now, then it was the right decision. Working software works. Laugh at it, learn from it, and let it go; repair what you can, when you can, but keep moving forward.

Second, learn to code naked. Whatever it is that you’re trying to do at the moment, share it. Open yourself up to code review, to criticism; exposure brings experience. Granted, you’ll meet some seagulls along the way, but eventually, you’ll figure out who’s there to help you grow as a developer. Foster those relationships.

Third, encourage people to grow; recognize that the same grace you desire for your coding mistakes is applicable to others as well. Be kind, be gentle, but be honest; seek to understand why they made the design choices they did, and be sensitive to the fact that if it works, it works. Sometimes we get caught up on trying to figure out the right way to do something, and ultimately end up doing nothing because it’s too difficult to implement it according to the textbook.

Life is too short to not enjoy what you do; try to share that joy without embarrassment.

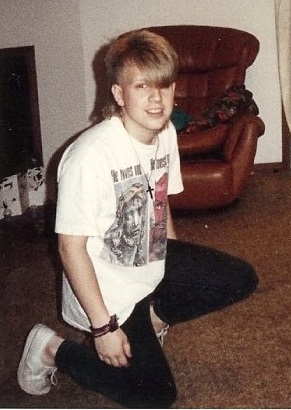

THIS is the most embarrassing picture of me from that time period. I thought being an actor was the best way to meet girls… Yes, those are tights I am wearing…

I’ve been reading Aaron Bertrand’s great series of blog posts on bad habits to kick, and have been thinking to myself: what are some good habits that SQL Server developers should implement? I spend most of my day griping about bad design from vendors, yet I hardly ever take the time to document what should be done instead. This post is my first attempt to do so, and it’s based on the following assumptions:

I’ve been reading Aaron Bertrand’s great series of blog posts on bad habits to kick, and have been thinking to myself: what are some good habits that SQL Server developers should implement? I spend most of my day griping about bad design from vendors, yet I hardly ever take the time to document what should be done instead. This post is my first attempt to do so, and it’s based on the following assumptions: