Very honored to be today’s guest blogger at Pinal Dave’s blog Journey to SQL Authority; check out my post here:

management

2014 Year In Review

Finally finding some time to sit down and write this post; of course I’m squeezing it in after work, and before my wife and son come home, so there’s no telling how far I’ll get. This post is probably best treated as a stream of consciousness effort, rather than my usual agonizing over every word. 2014 was a mixed bag of a year; lots of good stuff, and lots of not-so-good stuff; I’ll try to start with the good:

2014 Professional Highs

As I’ve mentioned before, I was promoted to management in my day job a few years ago; in October of 2014, my kingdom expanded. Instead of managing a team of SQL Server DBA’s, my department was consolidated with another small group, and I now manage the IT infrastructure for our Product Group. It’s not a huge jump, but it is an opportunity for me to get involved with more than just SQL Server and databases; I’m now managing a team of sysadmins as well, so I’m getting a crash course on virtualization, server administration, and networking. It’s been fun, but a bit challenging.

I haven’t neglected my SQL Server roots, however; I presented to over a dozen user groups & SQL Saturdays last year (which is a lot for full-time desk jockey). I ultimately delivered two killer presentations at Summit in November, which boosted my confidence tremendously after 2013’s less-than-stellar performance. Blogging was steady for me (23 posts on my blog), but I did have a chance to write a piece on Pinal Dave’s blog (Journey to SQL Authority); that was a great opportunity, and one I hope to explore more. In addition to blogging and community activity, I also finally passed the second test in the MCSA: SQL Server 2012 series (Administration; 70-462). I’m studying for the last test (Data Warehouse; 70-463), and then I need to start getting some virtualization certs under my belt.

Finally, a big professional step forward for me was that I became a Linchpin (part-time); I’ve had a great deal of respect for this team of SQL Server professionals over the years, and I was very blessed to be able to step in and help on a few projects this year. I’m hoping for more. It’s a great way to test the waters, even if I’m not ready to dive into full-time consulting yet.

2014 Professional Lows

I got nominated for Microsoft MVP (twice); I didn’t get it (twice).

2014 Personal Highs

Big year for travel for my wife and I; we went to Jamaica and Vancouver, as well as Nashville, Chattanooga, St. Louis, Charlotte, Seattle, Hilton Head, Myrtle Beach, and Ponte Vedra. We saw two killer shows: George Strait and Fleetwood Mac; I also got to see one of my favorite bands, The Old 97’s. Our son turned a year old, and it’s been a lot of fun watching him grown and discover new things. 2014 was a year of joy in a lot of ways….

2014 Personal Lows

2014 was also a year of sorrow for me; if you follow me on Facebook, you know how proud I am of my son. What became less well-known is that I have two teenage daughters from my previous marriage; they turned 17 and 15 this year. In September of 2013, my daughters decided that they didn’t want to spend as much time with me and their stepmother. Over the last year, I’ve had to come to terms with the fact that my daughters aren’t planning on changing that any time soon, and they have no desire to have a relationship with their brother. That’s a pain that I’ll never get over; I love all of my children, and all I can do is pray that someday things will change. The only reason I feel compelled to mention it publically is that I don’t want them to become invisible; I have three children, even if I don’t get to see two of them very often. I also feel like I’ve reached a turning point; I was VERY depressed last year because of this situation, and I’m ready to move forward in 2015.

Summary

2014 was more good than bad, but I’m looking forward to 2015. I’ve always believed that you should play the hand you’re dealt, and make the most of it. Life is good, and it’s only getting better.

#SQLPASS–Good people, bad behavior…

I’ve written and rewritten this post in my mind 100 times over the last couple of weeks, and I still don’t think it’s right. However, I feel the need to speak up on the recent controversies brewing with the Professional Association for SQL Server’s BoD. Frankly, as I’ve read most of the comments and discussions regarding the recent controversies (over the change in name, the election communication issues, and the password issues), my mind keeps wandering back to my time on the NomCom.

In 2010, when I served on the NomCom, I was excited to contribute to the electoral process; that excitement turned to panic and self-justification when I took a stance on the defensive side of a very unpopular decision. I’m not trying to drag up a dead horse (mixed metaphor, I know), but I started out standing in a spot that I still believe is right:

The volunteers for the Professional Association of SQL Server serve with integrity.

Our volunteers act with best intentions, even when the outcomes of their decisions don’t sit well with the community at large. However, we humans are often flawed in our fundamental attributions. When WE make a mistake, it’s because of the situation we are in; when somebody else makes a mistake, we tend to blame them. We need to move past that, and start questioning decisions while empathizing with the people making those decisions.

In my case, feeling defensive as I read comments about “the NomCom’s lack of integrity” and conspiracy theories about the BoD influencing our decision, I moved from defending good people to defending a bad decision. This is probably the first time that I’ve publically admitted this, but I believe that we in the NomCom made a mistake; I think that Steve Jones would have probably made a good Director. Our intention was good, but something was flawed in our process.

However, this blog post is NOT about 2010; it’s about now. I’ve watched as the Board of Directors continue to make bad decisions (IMO; separate blog forthcoming about decisions I think are bad ones), and some people have questioned their professionalism. Others have expressed anger, while some suggest that we should put it all behind us and come together. All of these responses are healthy as long as they separate the decisions made from the people making them, and that we figure out ways to make positive changes. Good people make mistakes; good people talk about behaviors, and work to address them.

So, how do we work to address them? The first step is admitting that there’s a problem, and it’s not the people. Why am I convinced that it’s not the people? Because every year we elect new people to the board, and every year there’s some fresh controversy brewing. Changing who gets elected to the board doesn’t seem to seem to stimulate transparency or proactive communication with the community (two of the biggest issues with the Professional Association for SQL Server’s BoD). In short, the system is not malleable enough to be influenced by good people.

I don’t really have a way to sum this post up; I wish I did. All I know is that I’m inspired by the people who want change, and it saddens me that change seems to be stunted regardless of who gets elected. Something’s gotta give at some point.

*************

Addendum: you may have noticed that I use the organization’s full legal name when referring to the Professional Association for SQL Server. Think of it as my own (admittedly petty) response to the “we’re changing the name, but keeping our focus” decision.

Managing a Technical Team: Building Better

Heard a great podcast the other day from the team at Manager Tools, entitled “THE Development Question”. I’m sorry to say that I can’t find it on their website, but it did show up in Podcast Addict for me, so hopefully you can pick it up and give it a listen. I’ll sum up the gist here, but it’s really intended to be a starting point for this blog post. In essence, Manager Tools says that when a direct approaches you (the manager) with a question, one of the best responses you can offer is another question:

Heard a great podcast the other day from the team at Manager Tools, entitled “THE Development Question”. I’m sorry to say that I can’t find it on their website, but it did show up in Podcast Addict for me, so hopefully you can pick it up and give it a listen. I’ll sum up the gist here, but it’s really intended to be a starting point for this blog post. In essence, Manager Tools says that when a direct approaches you (the manager) with a question, one of the best responses you can offer is another question:

“What do you think we should do?”

Their point is not that management is a game of Questions Only, but that leaders want to develop others and development comes through actions; employees have lots of reasons for asking questions, but a good manager should realize that employees need to be empowered and able to take action for most situations. If an employee is constantly waiting on approval from the manager, then the manager becomes the bottleneck.

Mulling on this a couple days made me realize that there’s a potential hazard for most new technical managers related to the issue of employee development; are we doing enough to make our employees better engineers than we were? Let me walk you through my thinking:

- Most new technical managers were promoted to their position from within their company, and it was usually because they were the best operator (i.e, someone who was skilled at their job as an engineer).

- Most new technical managers have a tough time separating themselves from their prior responsibilities, particularly if those prior responsibilities were very hands-on with a product\service\effort that’s still in use today (e.g., as a developer, John wrote most of the code for the current application; as a manager, John still finds himself supporting that code).

- If you were the best at what you did, that means that the people you now manage weren’t. Actual skill level is debatable, but most of us take a lot of pride in what we do. Pride can overemphasize our own accomplishments, while downplaying the accomplishments of others.

This is a problem for technical management, because the goal of a good manager is NOT to solve problems, but rather to increase efficiency. Efficiency is best achieved by distribution; in other words, you as a technical manager could learn how to improve your own technical skills by 10%, but if your employees don’t grow, your team’s not really making progress. On the other hand, if you invest in your directs’ growth and each f them improves their technical skills by 10%, it’s a bigger bang for your buck (unless you only have one employee; if that’s the case, polish your resume).

Here’s the kicker: Sacrificing your technical skills while building the skills of your employees will pay off more in the long run than continuing to build your own technical knowledge alone. You WANT your employees to be better engineers than you were because you gain the advantage of the increased skills that brings to the table distributed and magnified by the number of employees you have. I’m not saying that you should completely give up your passion for technology; it’s helpful for managers to understand the challenges their employee’s face without necessarily being an expert (that’s a fundamental principle of Lean Thinking; “go see” management). However, you should strive to be the least technical person on your team by encouraging the growth of the rest of your team.

So let me ask you: “What are you doing to develop your employees today?”

A tiny step in the right direction #SQLPASS

Ah, summertime; time for the annual “community crisis” for the Professional Association for SQL Server. I’ve tried to stay clear of controversies for the last couple of years, but it’s very hard to be a member of such a passionate group of professionals and not have an opinion of the latest subject d’jour. The short form of the crisis is that there’s questions about how and why sessions get selected to present at the highly competitive Summit this year (disclaimer: I got selected to present this year). For more details, here’s a few blog posts on the subject:

The point of my post is not to rehash the issue or sway your opinion, dear reader, but rather to focus on a single tiny step in the right direction that I’ve decided to make. One of the big issues that struck me about the whole controversy is the lack of a repeatable objective tool for speaker evaluations. As a presenter, I don’t always get feedback, and when I do, the feedback form varies from event to event, meeting to meeting. Selection committees are forced to rely on my abstract-writing skills and/or my reputation as a presenter; you can obfuscate my identity on the abstract, but it’s tough to factor in reputation if do that.

While I agree that there are questions about the process that should be asked and ultimately answered, there’s very little that I can do to make a difference in the way sessions get selected. However, as a presenter, and a chapter leader for one of the largest chapters in the US, I can do a little something.

- I am personally committing to listing every presentation I make on SpeakerRate.com, and soliciting feedback on every presentation. To quote Bleachers, “I wanna get better”.

- I will personally encourage every presenter at AtlantaMDF to set up a profile and evaluation at SpeakerRate for all presentations going forward.

- We will find ways to make feedback electronic and immediate at the upcoming Atlanta SQLSaturday so that presenters can use that information going forward.

- I will champion the evaluation process with my chapter members and speakers, and continue to seek out methods to improve and standardize the feedback process.

Do I have all of the right answers? No. For example, SpeakerRate.com seems to be barely holding on to life; no mobile interface, and a lack of commitment from its members seems to indicate that the site is dying a slow death. However, I haven’t found an alternative to provide a standard, uniform measure of presentation performance.

Do I think this will provide a major change to the PASS Summit selection? Nope. But I do think that a sea change has to start somewhere, and if enough local chapters get interested in a building a culture of feedback and evaluation, that could begin to flow up to the national level.

MaTT: The MARS framework for DBA’s

So, as usual, I’m struggling to sit down and write; I know I should (it’s good for the soul), but frankly, I’m struggling to put words to web page. As a method of jumpstarting my brain, I thought I would write about something simple and relevant to what I’m doing these days in my primary capacity: management.

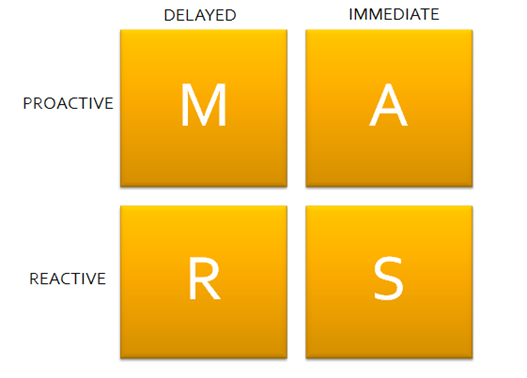

When I took over the reins of a newly formed department of DBA’s, I knew that I needed to do something quick to demonstrate the value of our department to our recently re-organized company. We’re a small division in our company, but we manage some relatively large databases (17 TB of data, with a relatively high daily change rate; approximately 10 TB of data change daily). My team was comprised of senior DBA’s who were inundated with support requests (from “I need to know this information” to “I need help cleaning up this client’s data”); while they had monitoring structures in place, it wasn’t uncommon for things to go unnoticed (unplanned database growth, poor performing queries, etc.). One of my first acts as a manager was to put in a system of classification I called MARS; all of our work as DBA’s needed to be categorized into one of four broad groups.

Maintenance, Architecture, Research, and Support

The premise is simple; by categorizing efforts, we could measure where the focus of our department was, and begin to allocate resources into the proper arenas. I defined each of the four areas of work as such:

- Maintenance – the efforts needed to keep the system performing well; backups, security, pro-active query tuning, and general monitoring are examples.

- Architecture – work associated with the deployment of new features, functionality, or hardware; data sizing estimates, upgrades to SQL 2012, installation of Analysis services are examples. To be honest, Infrastructure may have been a better term, but MIRS sounded stupid.

- Research – the efforts to understand and improve employee skills; I’m a former teacher, and I put a pretty high value on lifelong learning. I want my team to be recognized as experts, and the only way that can happen is if the expectation is there for them to learn.

- Support – the 800 lb gorilla in our shop; support efforts focus on incident management (to use ITIL terms) and problem resolution. Support is usually instigated by some other group; for example, sales may request a contact list from our CRM that they can’t get through the interface, or we may get asked to explain why a ticket didn’t get generated for a customer.

After about a year of data gathering, I went back and thought about the categories a bit more, and realized that I could associate some descriptive adjectives with the workload to demonstrate where the heart of our efforts lies. I took my cues from the JoHari window, and came up with the two axes: Actions: Proactive – Reactive, and Results: Delayed-Immediate. I then arranged my four categories along those lines, like so:

In other words, Maintenance was Proactive, but had Delayed results (you need to monitor your system for a while before you grasp the full impact of changes). Research was more Reactive, because we tend to research issues that are spawned by some stimulus (“what’s the best way to implement Analysis Services in a clustered environment?” came up as a Research topic because we have a pending BI project).

Immediate results came from Architectural changes; adding more spindles to our SAN changed our performance quickly, but there was Proactive planning involved before we made the change. Support is Reactive, but has Immediate results; the expectation is that support issues get prioritized, so we try to resolve those quickly as part of our Operational Level Agreements with other departments.

After a couple of months looking at our work load (using Kanban), I see that we still spend a lot of time in Support, but that effort is trending downward; I continue to push Maintenance, Architecture, and Research over Support, and we’re becoming much more proactive in our approaches. I’m not sure if this quadrant approach is the best way to represent workload, but it does give me a general rule-of thumb in helping guide our efforts.

Back on the trail…. #sqlsatnash

I realize that I should probably be blogging about my New Year’s resolutions, but meh… I’ve been super busy surviving the holidays. So busy in fact that I’ve failed to mention that I’ll be presenting at the SQLSaturday in Nashville on January 18, 2014. I actually got selected to present TWO topics, which is HUGE for me. Hoping that I can refine a presentation, and get ready for our own SQLSaturday in Atlanta.

Working with “Biggish Data”

Most database professionals know (from firsthand experience) that there continues to be a “data explosion”, and there’s been a lot of focus lately on “big data”. But what do you do when your data’s just kind of “biggish”? You’re managing Terabytes, not Petabytes, and you’re trying to squeeze out as much performance out of your aging servers as possible. The focus of this session is to identify some key guidelines for the design, management, and ongoing optimization of “larger-than-average” databases. Special attention will be paid to the following areas: * query design * logical and physical data structures * maintenance & backup strategies

Managing a Technical Team: Lessons Learned

I got promoted to management a year ago, and despite what I previously believed, there were no fluffy pillows and bottles of champagne awaiting me. My team liked me, but they didn’t exactly stoop and bow when I entered the room. I’ve spent the last year relearning everything I thought I knew about management, and what it means to be a manager of a technical team. This session is intended for new managers, especially if you’ve come from a database (or other technical) background; topics we’ll cover will include:*How to let go of your own solutions. *Why you aren’t the model you think you are, and *Why Venn diagrams are an effective tool for management.

MaTT: Entropy

Decided to take a detour today in my blogging thoughts (it is Friday, after all), and opted to revisit the issues of managing a technical team (MaTT); today’s topic: Entropy.

Decided to take a detour today in my blogging thoughts (it is Friday, after all), and opted to revisit the issues of managing a technical team (MaTT); today’s topic: Entropy.

en·tro·py

/ˈentrəpē/

Noun

- A thermodynamic quantity representing the unavailability of a system’s thermal energy for conversion into mechanical work, often…

- Lack of order or predictability; gradual decline into disorder.

Simply put, processes decay over time. A good manager will recognize this, and learn to intervene when those processes begin to break down. In contrast, code lives on forever (unless someone steps in to change it).

Let me give an example; about a year and a half ago, I implemented Kanban as a method of managing our workflow in the production environment. My team quickly adapted to it, and it became very easy to see exactly what people were working on, and what was getting accomplished. I thought “my job here is done”, and moved on to other things, occasionally touching base with the Kanban board to see what was going on.

This week, I realized that the process had degenerated; sure, my team was still using the board to report what they had done for the day. However, they’ve gotten in the habit of solving the problem, and then creating the card in the Done pile. Entropy. I am no longer able to predict or measure what is being done or what needs to be done.

I’m out next week (hoping my son is born by the end of the week), but when I return, I need to intervene and work toward cleaning up the process. While I firmly believe that I should trust my team and encourage them to make the right decision, part of the management process is learning when to intervene in order to shore up a process that is decaying.

MaTT: You have to start somewhere

So, January came and went, and no post from me. I continue to suffer from writer’s block, but I’ve finally cobbled together enough ideas that I feel like I can put a couple of quick posts out there. I’m still struggling with learning how to manage a technical team (MaTT) as opposed to being a technical person, but here’s another concept I’m beginning to grasp.

You have to start somewhere.

When I began managing my team, I was tempted to rush in and save the day. I know where a lot of the problems are, and I know which ones are big, and which ones are not. I kept thinking that if I could just motivate the team to start attacking the problem, then we’d be sitting pretty in a year.

I was wrong.

Most people are already motivated to do their jobs; if they’re not, then they’re in the wrong position, and it’s hurting them as well as hurting the company. What a team is usually looking for in a manager is to help them make priority decisions, and to back them up when they need things to change. Here’s the conundrum: Technical people often (logically) focus on changing the things that hurt them the most. Your DBA may say “I keep having to babysit this query for the boss because it’s slow, and it’s slow because the developers don’t know how to normalize a database; can we refactor everything?”. Your developers may say “If we had more time to rebuild everything, we could fix that query; can we hire another person or put these features on hold so we could tune everything?”. Your boss may say “We need to make a profit; what’s the most cost-effective way to manage our database architecture moving forward?”

If you focus your energy on addressing the technical issues without giving consideration to the profitability of your company, you’re spinning your wheels. However, you MUST figure out a way to ease the pain of your technical team by addressing their concerns. It’s no secret that I’m a Lean/Agile kind of guy; I truly believe that these philosophies can help balance the scales between support/development/operations, but you have to start somewhere.

“Somewhere” for me is the small fixes; don’t tackle the big projects head-on. Focus on being successful at a couple of small things (e.g., reduce the number of support calls in a measurable fashion, or refactor some small but essential bit of code). Make sure that these changes are measureable, and make sure that you report the changes to your boss AND to your team. This accomplishes two things:

- It shows measurable progress (in my experience, bosses love metrics), and

- It encourages your team by giving them a couple of quick successes.

If your team doesn’t see progress, then in their mind, “nothing is being done”. Your boss wants to know how you’re improving efficiency and effectiveness in terms of dollar signs; your team wants to know that they’re solving a technical problem. Make sure you can address both of those needs.

More to come.